- Home

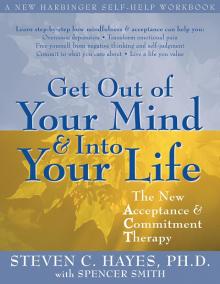

- Steven C. Hayes

Get Out of Your Mind and Into Your Life Page 2

Get Out of Your Mind and Into Your Life Read online

Page 2

This metaphor is intended to illustrate the difference between the appearance of psychological problems and their true substance. In this metaphor, the war looks and sounds much the same whether you are fighting it or simply watching it. Its appearance stays the same. But its impact—its actual substance—is profoundly different. Fighting for your life is not the same as living your life.

Ironically, our research suggests that when the substance changes, the appearance may change as well. When fighters leave the battlefield and let the war take care of itself, it may even subside. As the old slogan from the 1960s put it: “What if they fought a war and nobody came?”

Compare this metaphor with your own emotional life. ACT focuses on the substance, not the appearance, of problems. Learning to approach your distress in a fundamentally different way can quickly change the impact it has on your life. Even if the appearance of distressing feelings or thoughts does not change (and who knows, it might), if you follow the methods described in this book, it is far likelier that the substance of your psychological distress, that is, its impact, will change.

In that sense, this is not a traditional self-help book. We aren’t going to help you win the war with your own pain by using new theories. We are going to help you leave the battle that is raging inside your own mind, and to begin to live the kind of life you truly want. Now.

SUFFERING: PSYCHOLOGICAL QUICKSAND

This counterintuitive idea of abandoning the battlefield rather than winning the war may sound strange, and implementing it will require a lot of new learning, but it is not crazy. You know about other situations like this. They are unusual, but not unknown.

Suppose you came across someone standing in the middle of a pool of quicksand. No ropes or tree branches are available to reach the person. The only way you can help is by communicating with him or her. The person is shouting, “Help, get me out,” and is beginning to do what people usually do when they are stuck in something they fear: struggle to get out. When people step into something they want to get out of, be it a briar patch or a mud puddle, 99.9 percent of the time the effective action to take is to walk, run, step, hop, or jump out of trouble.

This is not so with quicksand. To step out of something it is necessary to lift one foot and move the other foot forward. When dealing with quicksand, that’s a very bad idea. Once one foot is lifted, all of the trapped person’s weight rests on only half of the surface area it formerly occupied. This means the downward pressure instantly doubles. In addition, the suction of the quicksand around the foot being lifted provides more downward pressure on the other foot. Only one result can take place: the person will sink deeper into the quicksand.

As you watch the person stuck in the quicksand, you see this process begin to unfold. Is there anything you can shout out that will help? If you understood how quicksand works, you would yell at the person to stop struggling and to try to lie flat, spread-eagled, to maximize contact with the surface of the pool. In that position, the person probably wouldn’t sink and might be able to logroll to safety.

Since the person is trying to get out of the quicksand, it is extremely counterintuitive to maximize body contact with it. Someone struggling to get out of the mud may never realize that the wiser and safer action to take would be to get with the mud.

Our own lives can be very much like this, except the quicksand we find ourselves in, often is, in one sense, endless. Exactly when will the quicksand of a traumatic memory completely vanish? At what moment will the painful quicksand of past criticism from parents or peers disappear? Right now think of a psychological aspect of yourself that you like the least. Take a moment to consider this question. Now ask yourself, “Was this an issue for me last month? Six months ago? A year ago? Five years ago? Exactly how old is this problem?”

Most people find that their deepest worries are not about recent events. Their deepest worries have been lurking in the background for years, often many years. That fact suggests that normal problem-solving methods are unlikely to be successful. If they could succeed, why haven’t they worked after all these years of trying? Indeed, the very longevity of most psychological struggles suggests that normal problem-solving methods may themselves be part of the problem, just as trying to get free is a huge problem for someone stuck in quicksand.

You’ve picked up this book for a reason. Our guess is that you find yourself in some sort of psychological quicksand and you think you need help freeing yourself. You’ve tried various “solutions” without success. You’ve been struggling. You’ve been sinking. And you’ve been suffering.

Your pain will be an informative ally on the path that lies ahead. You have an opportunity that someone who hasn’t experienced psychological pain doesn’t have, because it is only when common sense solutions fail us, that we become open to the counterintuitive solutions to psychological pain that modern psychological science can provide. As you become more aware of how the human mind works (particularly your mind), perhaps you will be ready to take the path less traveled. Haven’t you suffered enough?

We haven’t written this book to help you free yourself from the quicksand you find yourself in, but to get with it. We wrote to relieve your suffering and empower you to lead a valued, meaningful, dignified human life. Psychological issues that you’ve previously struggled with may technically remain (or they may not), but what will it matter if they remain in a form that no longer interferes with you living your life to the fullest?

THE UBIQUITY OF HUMAN SUFFERING

This book starts from a different set of assumptions than most popular psychology books do. We indicated what that difference is in the first two words of this introduction: People suffer. We don’t assume that left to their own devices, normal human beings are happy and that only an odd history or a broken biology disturbs the peace. We assume instead that suffering is normal and it is the unusual person who learns how to create peace of mind. Why this is so is a puzzle; this book is about that puzzle.

It’s remarkable how many problems human beings have that nonhumans can literally not imagine. Consider the data on suicide. It occurs in every human population, and serious struggles with suicide are shockingly commonplace. Throughout your lifetime, you have about a fifty-fifty chance of struggling with suicidal thoughts at a moderate to severe level for at least two weeks (Chiles and Strosahl 2004). Almost 100 percent of all the people on the planet will at some point in their life contemplate killing themselves. Preverbal children do not make suicide attempts but even very young, newly verbal children occasionally do (Chiles and Strosahl 2004). Yet we have little reason to believe that any nonhuman animals deliberately kill themselves.

That basic pattern repeats itself in problem area after problem area: Most human beings struggle, even in the midst of what appear to be successful lives. Ask yourself this question: How many people do you know really well who don’t experience periods in which they struggle with serious psychological or social problems, relationship issues, problems at work, anxiety, depression, anger, self-control issues, sexual problems, fear of death, and so on? For most people, a list of such contented acquaintances will be very short indeed, perhaps even empty.

The scientific data on human problems confirms this impression. Let’s just mention a few random facts. About 30 percent of all adults have a major psychiatric disorder at any given point in time, about 50 percent will have such a disorder at some point in their lives, and nearly 80 percent of these will have more than one serious psychological problem (Kessler et al. 1994). Americans spend huge sums of money in their efforts to alleviate their psychological pain.

For example, antidepressants are a ten-billion-dollar industry, even though their average impact on depression is only 20 percent better than a placebo, too small to be clinically significant (Kirsch et al. 2002). Indeed, our consumption of antidepressants is so high that our rivers and streams have become polluted with them, contaminating the fish we eat (Streater 2003). But these statistics, sad though they are, gr

ossly underestimate the extent of the problem. When people are given open access to mental-health care, only about half of those who seek help are diagnosed with a serious mental-health disorder (Strosahl 1994). The other half are having problems at work, or in their marriages, or with their children, or they suffer from the lack of purpose in their lives, what the philosophers call “existential dread,” or from “angst,” which is a strong ever-present feeling of apprehension and anxiety.

Marriages, for example, are probably the most important voluntary adult relationship most humans enter into, yet about 50 percent of all marriages end in divorce and remarriages are no better (Kreider and Fields 2001). The dismal statistics on fidelity, abuse, and marital happiness show that many intact marriages are based on unhealthy relationships (Previti and Amato 2004).

This litany could go on and on easily. By the time all of the major behavioral problems human beings face are added together, in effect, it is “abnormal” not to experience significant psychological struggles.

How can this be? We could understand it if we were discussing people without resources in ravaged societies. If a Sudanese child must hide from the violence of a rebel militia, we can easily appreciate her misery. If a grieving mother in Indonesia loses everything to a tsunami, her suffering is horrible but, given her horrific circumstances, it is to be expected. This is mostly not true for the people who read this book, as most of us realize when we compare our lives to the lives of those suffering from war or horrendous natural disasters. Yet in many problem areas, people who are intelligent and successful are not necessarily happier than their less fortunate counterparts in other parts of the world. People who live in countries with spectacularly successful economies do not have fewer social or interpersonal problems (e.g., suicide) than their counterparts in more difficult economic circumstances (Chiles and Strosahl 2004). How can this be?

Apply this question to your own life. Isn’t it true that the things you are struggling with and trying to change tend to persist, even though you are competent and able in so many other areas of your life? Isn’t it true that you’ve tried to solve these problems, but so far have failed to find a real solution? Indeed, you may have already tried many solutions…and yet here you are buying another book designed to help you. How can this be?

We ask you to keep these questions in mind as you read this book: Why is human suffering so pervasive, why is yours so difficult to change, and what can you do about it? The rest of this book will explore these questions in detail. We think we can supply at least part of the answers.

We don’t ask these questions from an arrogant or critical perspective. This book won’t blame you for your troubles, conveying the not-so-subtle message that your life would be fine if only you tried harder. This book comes from a stance of compassion and identification; it has emerged from our own struggles and those of our patients. The questions above are those we’ve asked ourselves, sometimes from the depth of despair. We believe that science has begun to provide an unexpected answer however; and it is one that can be directly helpful to you.

MINDFULNESS, ACCEPTANCE, AND VALUES

ACT is not a set of idiomatic phrases or wise sayings that will lead you toward a personal revelation. Although some of the principles in ACT are as old as history, there is one major component of the therapy that is new. ACT is based on a new model of human cognition. This model underlies specific techniques presented in this book, which are designed to help you change your approach to your problems, and the direction in which your life has been going. These techniques fall into three broad categories: mindfulness, acceptance, and values-based living.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a way of observing your experience that has been practiced in the East through various forms of meditation for centuries. Recent research in Western psychology has proven that practicing mindfulness can have notable psychological benefits (Hayes, Follette, and Linehan 2004). In fact, mindfulness is currently being adopted as a means of enhancing treatment in a number of different psychological traditions in the West (Teasdale et al. 2002).

A large part of our approach has to do with mindfulness. What ACT brings to this ancient set of practices is a model of the key components of mindfulness and a set of new methods to change these components. Weeks, months, or years of meditation, helpful as they can be, are not the only practices that can increase mindfulness, and in today’s busy world, new means are needed to augment those that evolved in another, slower millennium.

In this book we will help you learn to see your thoughts in a new way. Thoughts are like lenses through which we look at our world. We all have a tendency to cling to our particular lens and allow it to dictate how we interpret our experiences, even to the point of dictating who we think we are. If you are now stuck in the lens of your psychological pain, you may say things to yourself like, “I’m depressed.” In this book we will help you see the dangers of holding on to thoughts of that kind, and we will provide concrete methods to help you avoid those dangers.

As you free yourself from the illusions of language, you will learn to become more aware of the many verbal lenses that emerge every day, and yet not be defined by any one of them. You will learn how to undermine your attachment to a particular cognitive lens in favor of a more holistic model of self-awareness. Using specific techniques, you will learn to look at your pain, rather than seeing the world from the vantage point of your pain. When you do that, you will find there are many other things to do with the present moment besides trying to regulate its psychological content.

Acceptance

ACT draws a clear distinction between pain and suffering. Because of the nature of human language, when we encounter a problem, our general tendency is to figure out how to fix it. We try to get out of the quicksand. In the outside world this is very effective 99.9 percent of the time. Being able to figure out how to rid ourselves of undesirable events, such as predation, cold, pests, or flooding, was essential in establishing the human race as the dominant species on our planet.

It is an unfortunate consequence of the way our minds work, however, that we try to use this same “fix-it” mentality when it comes to understanding our internal experiences. When we encounter painful content within ourselves, we want to do what we always do: fix it up and sort it out so that we can get rid of it. The truth of the matter (as you have likely experienced) is that our internal lives are not at all like external events. For one thing, humans live in history, and time moves in only one direction, not two. Psychological pain has a history and, at least in that aspect, it is not a matter of getting rid of it. It is more a matter of how we deal with it and move forward.

The “acceptance” in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy is based on the notion that, as a rule, trying to get rid of your pain only amplifies it, entangles you further in it, and transforms it into something traumatic. Meanwhile, living your life is pushed to the side. The alternative we will teach in this book is a bit dangerous to say out loud because right now it is likely to be misunderstood, but the alternative is to accept it. Acceptance, in the sense it is used here, is not nihilistic self-defeat; neither is it tolerating and putting up with your pain. It is very, very different than that. Those heavy, sad, dark forms of “acceptance” are almost the exact opposite of the active, vital embrace of the moment that we mean.

Most of us have had little or no training in active forms of acceptance so we suggest that you thank your mind for whatever it says this term might mean, but don’t try to do anything with it right now. This is hard to describe, and learning to be willing to have and live your own experience is something we will focus on quite a bit later in the book. In the meantime, we ask for your patience and openness—and a bit of skepticism about what your mind might right now be guessing we mean.

Commitment and Values-based Living

Are you living the life you want to live right now? Is your life focused on what is most meaningful to you? Is the way you live your life characterized by

vitality and engagement, or by the weight of your problems?

When we are caught in a struggle with psychological problems we often put life on hold, believing that our pain needs to lessen before we can really begin to live again. But what if you could have your life be about what you want it to be about right now, starting this moment? We don’t ask you to believe that this is so, but merely to be open to the possibility it is so, open enough that you are willing to work with this book.

Getting in touch with the life you want to live and learning how to bring your dreams to life in the present isn’t easy because your mind, like all human minds, will spring trap after trap, throw up barrier after barrier. In chapters 1 to 10, you will learn how to free yourself from those traps and how to dissolve those barriers. In chapters 11 to 13 we will discuss what you really want your life to be about, and we will show you how to complete the process of shifting from useless mental management to life engagement.

At this point we aren’t asking you to agree with any of the claims being made or for you to say you understand any of the methods we have just begun to describe. We ask only for your engagement with a journey fundamentally focused on the puzzle of your suffering and that of others. This journey seeks a fundamental change in the very game being played, not just a new strategy for winning it. ACT is not a panacea, but the scientific results are both broad and positive (see appendix). We believe that we can help you take advantage of this new knowledge.

By all means, bring your skepticism, even your cynicism, along for the ride. They will not be harmful, provided you are willing to apply the methods you will learn even to that skepticism and cynicism. And bring your hopes and ability to believe along, as well, although they will not necessarily be helpful until they too are considered from the point of view of the methods to be described. You are a whole person, and all of your experiences, thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, and behavioral predispositions are welcome to come along on this journey of discovery.

Get Out of Your Mind and Into Your Life

Get Out of Your Mind and Into Your Life